Overview

This article will cover the difference between earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) and adjusted earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (AEBITDA). Market valuations in the PEO industry are typically based on a multiple of EBTIDA or AEBITDA. We will also cover the variables that impact valuation and cash earnings at the close of a transaction.

When reviewing the analytics for www.netprofitgrowth.com, we’ve noted that our highest viewed article for the last two months was from three years ago regarding EBITDA Add Backs. You may view the original article by clicking here). Since this is a popular topic among our readers, a short follow up piece providing additional insight was warranted. The original article covers the importance of EBITDA add backs, and the subsequent effect it has on valuations. This article will cover some additional factors that will impact market valuation, purchase price, and the actual amount of cash a seller will receive at closing, and in totality. These factors will be covered individually below and will be recapped with an example at the end of the article.

Run-Rate

Some sellers will request that the buyer base their valuation multiple off a run-rate in lieu of the trailing twelve months (TTM). Whether or not a buyer grants this request is on a case by case basis. There will need to be justification for a buyer to agree to this request. For example, if a seller recently experienced a growth spurt, it would be in the seller’s best interest to request the valuation be based off a six-month run-rate. This scenario would allow the seller to capitalize on its recent growth.

Please note that there is a distinction between basing a valuation off a six-month run rate and pro forma projections. Buyers will typically not give credit for a pro forma illustrating accounts that might close in the future. Buyers may consider giving the seller the benefit of determining the valuation through annualizing the trailing six month’s performance. For sellers that have experienced significant growth in the previous two quarters, this would be advantageous to their ultimate valuation. Moreover, this method can be justified by the purchaser because it is based on historical performance, albeit six months.

Equity Roll

Most deals, not all, have an equity roll included within the deal points. The average equity roll we have seen when reviewing deals hovers between 25% and 35%, though this may vary. The main reason a buyer requests an equity roll is to ensure the seller has a vested interest with the continuance of business performance. A seller should be cognizant that when they roll equity, that money is reinvested into the business and that amount will not be paid out at the close of the transaction.

However, the seller can significantly up their personal earnings from the transaction through an equity roll. For example, if an owner sells their PEO at a 5X multiple and rolls 30% equity, they stand to make significantly more on the equity roll once the investor exits the business. If for example, the investor is purchasing several PEOs and exits the investment at a 12X, the PEO owner has more than doubled the value of their rolled equity. As always, there is an element of risk associated with rolling equity (i.e. the PEO holdings devalues) but that typically is not the case.

Earn-out

Many PEO transactions will have an earn-out provision within the contract, though not all deals mandate an earn-out from our experience. An earn-out, like an equity roll, is a mechanism for the buyer to stimulate performance from the seller. It can also act as a bridge between deal points where the buyer and seller haven’t found common ground. An earn out is a portion of the purchase price that is contingent on some performance stipulations. This could take the form or growth, profit, etc.

Hypothetically, let’s assume that a seller asks a buyer to base the valuation on a run-rate, and the buyer doesn’t feel overly comfortable with the run-rate number. The two parties may come to an agreement where the buyer bases the valuation on the run-rate, however, part of the purchase payout will be held back for a year or two. This is to ensure that the run-rate and associated profit equate to the amount the seller is illustrating. Other examples of earn-outs could be revenue growth, profit increase requisites, client retention, etc. Earn-outs can be used to help negotiate a number of gaps between buyers and sellers.

Working Capital

Working capital is often a point of negotiation in deals. Owners may view the cash in the business as their money. Whereas buyers look to have a suitable amount of working capital post-acquisition to operate the business. The last thing that a buyer wants to do after buying a company is pour more money into the company. Each party should come together and negotiate a suitable amount of working capital to run the business post-acquisition.

Debt-Free

Most buyers want to purchase a company that is debt-free. Buyers do not want to purchase an asset for millions of dollars only to be saddled with additional debt within the business. Therefore, most buyers will request that the business be purchased debt-free. This means that either the business or the owner will pay off any debt at the time of transaction. This is typically a reasonable request but could detract from the earning of an owner if the PEO is heavily leveraged.

Recap of Important Factors

Below is a recap of the items that can impact the valuation and payout PEO ownership receives.

- EBITDA vs. AEBITDA: as covered in our original article, a PEO owner would benefit from reviewing any legitimate EBITDA add backs prior to entering the market. These add backs, once applied to the purchase multiple, could drive a substantially higher market valuation and purchase price.

- Run-Rate: if a PEO has experienced a significant uptick in EBITDA within the last two quarters, it should request that its final valuation/purchase price be based off a run-rate in lieu of the TTM.

- Equity Roll: Many deals require an equity roll between 25% and 35% from stakeholders. A PEO owner should understand the degree of risk with rolling equity, but typically the owner will increase their earnings through rolling a portion of equity via the investors exit at a higher multiple.

- Earn-Out: Many deals will include an earn-out provision to better align the interests of the seller and buyer. Earn-outs often bridge the gap between deal points with the buyer/seller. Earn-out provisions should be scrutinized to ensure that they are fair to both parties involved.

- Working Capital: working capital is a typical negotiation point. Some say that a business should be sold with no working capital, others say that it is requisite for the business to come with working capital. It is advised that both parties determine the appropriate amount of working capital requisite to run the business. This mitigates the investor having to pour working capital into the business and ensures that the buyer isn’t leaving unnecessary money in the business.

- Debt-Free: most investors want a debt-free PEO at the time of purchase. Sellers should understand the capital required to make the organization debt-free at the time of purchase.

Final Thoughts & Example

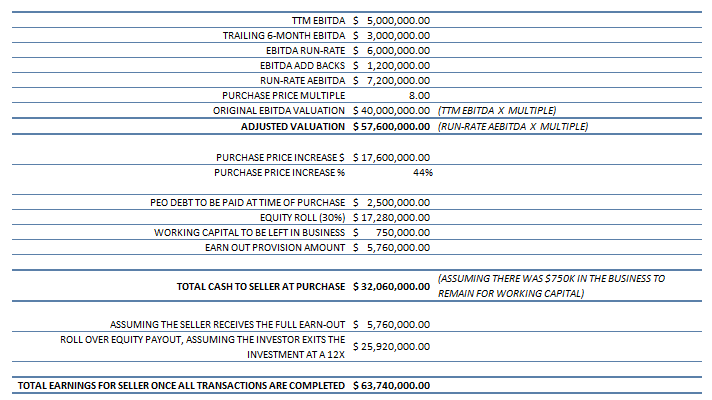

Now that we’ve reviewed some of the components that may impact a deal’s valuation, let’s take a look at the scenario below in Figure 1 to provide additional color. In this example, the trailing twelve months (TTM) EBITDA for the PEO is $5m. If the purchaser agrees to utilizing a run-rate for the last 6-months, the EBITDA would be revised to $6m. After EBITDA add backs, this number would be adjusted up another $1.2m. This end result in an AEBITDA of $7.2m. Utilizing an 8X multiple, this would increase the purchase price from $40m ($5m EBITDA) to $57.6m ($7.2m AEBITDA) or by 44%.

The below example assumes that the PEO had $2.5m in debt which needed to be paid off at the time of purchase. It also assumes that the buyer expects the seller to roll 30% of their equity and leave $750K within the business for working capital. Finally, this scenario stipulates a 10% earn-out provision within the deal. Once we factor in these elements, the total cash paid to selling ownership at the time of transaction equates to roughly $32m.

If the seller obtains the earn-out provision and if the buyer sells its PEO interests in 5 years at a 12X, the PEO ownership would make $5.76m with the earn-out and $25.92m from the equity roll (without even factoring in organic growth, synergies, etc. which could drive the earnings higher) at the time of the investor’s exit. In total, the PEO seller in this scenario would make a total of $63.74m in this deal prior to taxes. When these total earning are applied to the original TTM EBITDA of $5m, this equates to an ultimate value of 12.75X on the TTM EBITDA due to the deal mechanics and 2nd bite of the apple.

Figure 1

Understanding the factors that can add or detract from a PEO transaction will help set realistic expectations and prepare ownership for deal-point negotiations. Not knowing these factors could be materially detrimental to the seller… and if you don’t know, now you know.

Author

Rob Comeau is the Featured Author of this online PEO Publication and the CEO of Business Resource Center, Inc. BRC is a business consulting and M&A advisory firm to the PEO and investment communities. To reach Rob, you may visit BRC’s website at www.biz-rc.com or email him at rob.comeau@biz-rc.com.